A recent blog on an automated business-scorecard site helpfully suggests 18 key performance indicators that you should track. Along with 13 bonus performance indicators. And a link to another 37 indicators. The list faithfully follows the structure of the balanced scorecard popularized by Kaplan and Norton: seven financial indicators, five customer indicators, three process indicators, and three human-resources indicators.

There are two problems with this kind of prescription for managing small-business performance. First, there is no way all 18 of the success factors that these indicators measure are equally important in explaining important business outcomes like sales, cash flow, and profit. Pareto – he of the 80-20 rule – was right that, no matter how complex the outcome, there will always be only a few success factors that are truly vital. In terms of modern information theory, most of the information in an outcome like cash flow will be contained in the indicators for just a few causal factors that affect it. So why should a time-oppressed small business scramble to measure all 18 (or 31 or 68)?

Second, how can a standard list of indicators capture all the unique strategies that successful small businesses pursue? A close look at the list reveals indicators like days sales outstanding, customer acquisition cost, product defect rate, and employee turnover – all valuable in other contexts but none close to capturing a unique strategy. The problem is that indicators like these are downstream measures of success, not too different from the sales, cash flow, or profit outcomes that business owners need to shape. In short, standard performance indicators are not prescriptive.

Which of the following might really make your sales operation succeed – minimizing customer acquisition cost, maximizing sales calls, or perhaps focusing on calls with two hours of prep time for one segment of the target market and focusing on targeted events for the other segment of that market? Only the latter starts to look like a strategy you might actually implement – but you’ll never find a standard indicator for it.

Or which, to take another example, will make your product the best offering on the market? Maximizing customer satisfaction scores? Minimizing defect rates? Or something more like features in which key customers have invested at least an hour to discuss with you? Once again, no standard indicator is likely to reflect the kind of tactic you might actually implement.

What the examples of quantities that might really describe an effective strategy have in common is high specificity. That makes sense – successful tactics are usually unique or at least unusual. Such specificity poses a challenge of its own, however. We are unlikely to hit on the specific tactics that will work for our business right away. We need to experiment. And that means investment in indicators for a lot of the tactics we try out will be wasted.

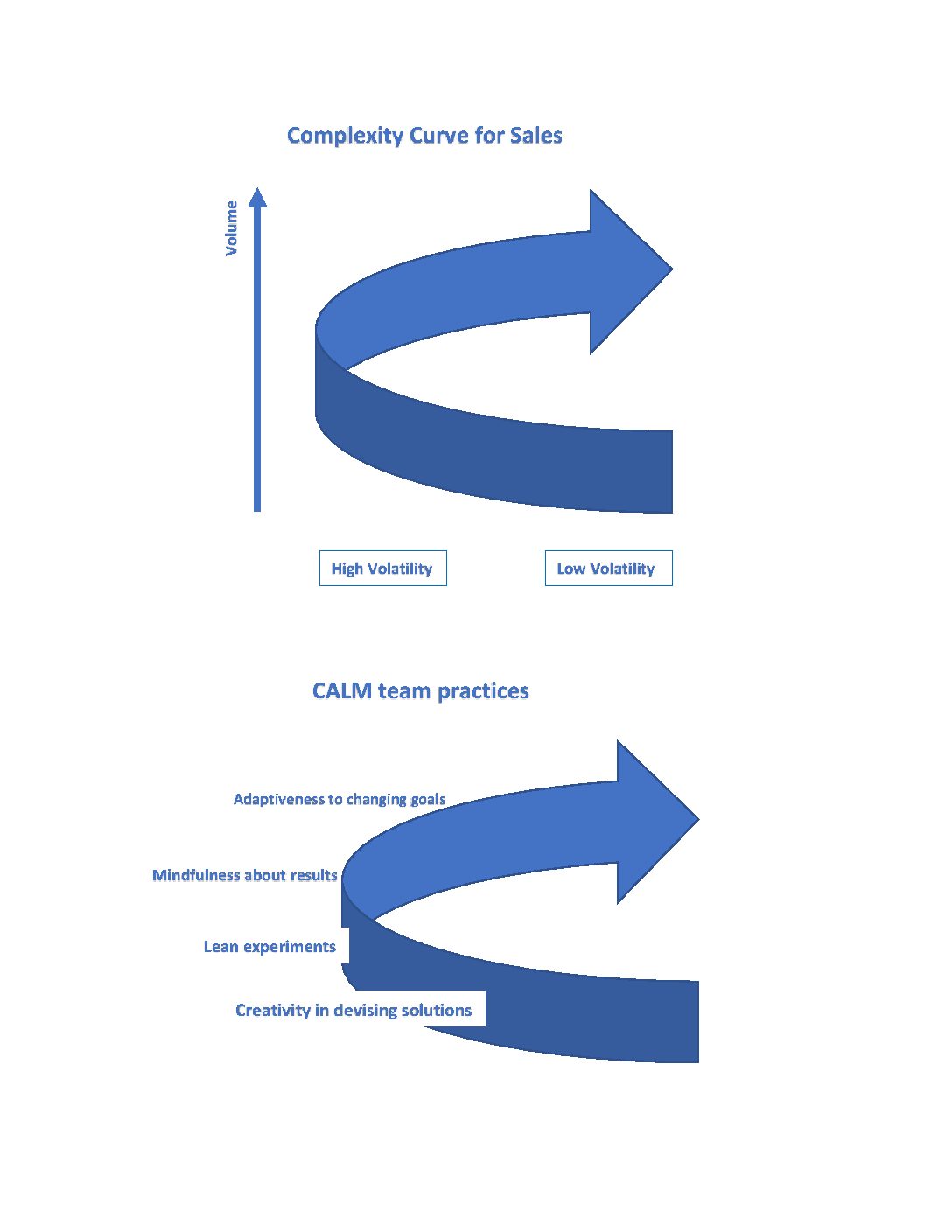

There is a better way. Put off investment in precise measures of specific tactics and strategies until you know they are working. (Yes, this advice is coming from a performance-metrics guy.) By all means use rough estimates to determine whether better- and worse-than-expected efforts correspond to better- and worse-than-expected outcomes. But keep your measurement systems lean while you experiment.