Impact scorecards help you improve business outcomes by measuring the effectiveness of your strategy as well as execution. After all, it doesn’t matter how well you execute a strategy if it’s the wrong strategy for hitting your goals.

The secret is to test assumptions about impact, not just performance. Using alternative scenarios, impact scorecards test the impact of strong strategy execution by showing how well your strategy explains high-performance as well as low-performance outcomes. This makes them unique. No other scorecard system increases your predictive power over time using alternative scenarios.

But why should testing assumptions about impact and not just performance make such a difference? Performance assumptions, it turns out, just don’t say enough about the future to help you learn from what happens. For example, most fitness programs combine exercise and diet. A typical performance assumption tells you how much weight you should expect to lose under a particular diet and exercise regime. What if you cheat just a little on your diet and miss your weight target by a mile? Did you miss your target just because of that potato or might the program assumptions be unrealistic? There’s no way to tell.

If you lay out alternative weight-loss assumptions in scenarios where you cheat on your diet or skip exercise, however, you can learn a lot no matter how well you execute. Say that you miss your exercise sessions and your weight loss (or gain) chimes with the assumption for a low-exercise scenario. Then your program is probably right and you need to get to the gym. But if there is a big gap between your actual weight loss and the low-exercise scenario, then your program is wrong about the sensitivity of your weight to exercise. It may just be worth skipping a workout and eating better.

Assumptions about impact say more about the future than assumptions about performance because impact assumptions let you work out what outcome you should have expected in any execution scenario. And the gap between what actually happens and what you should have expected given your assumptions is a direct measure of how well those assumptions reflect reality.

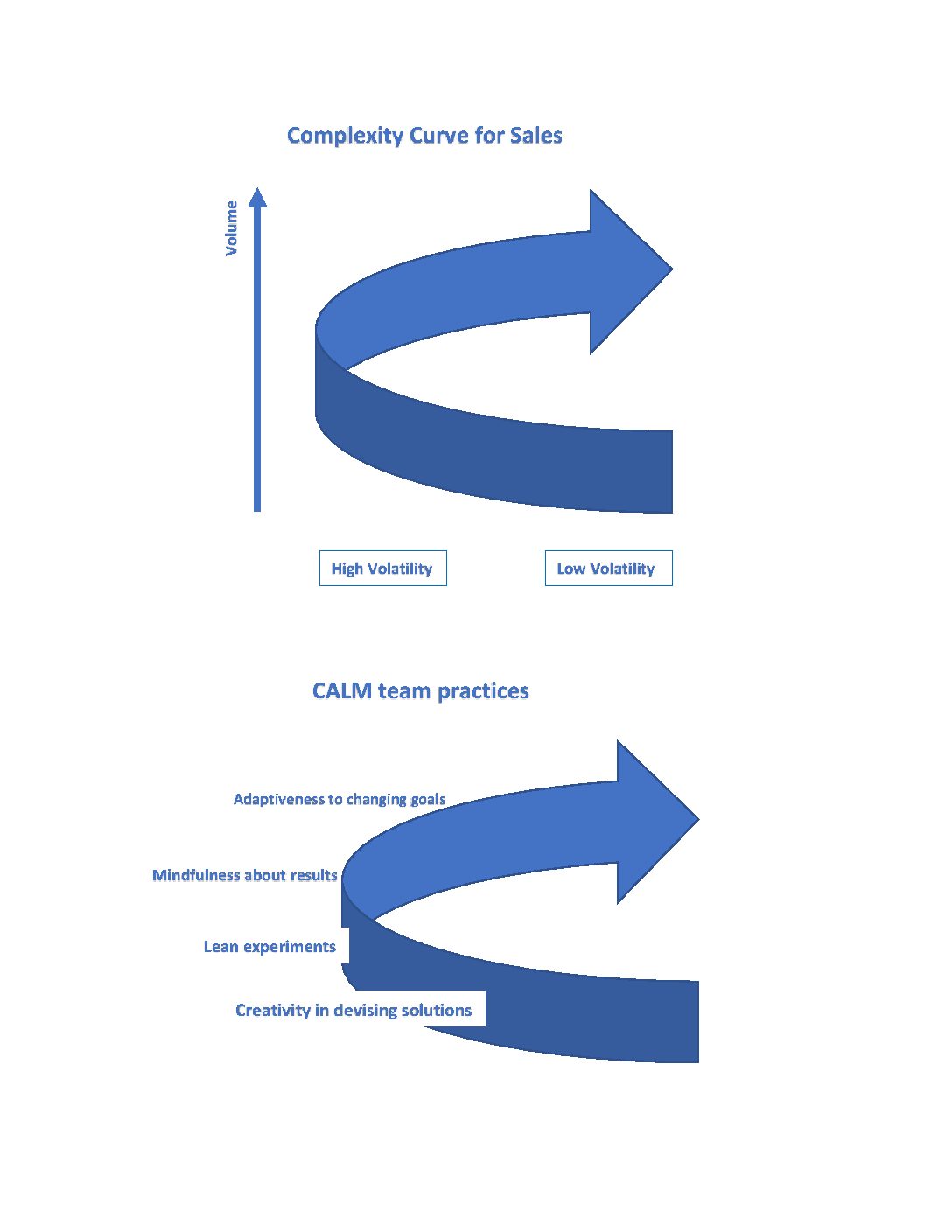

Say, for example, you think the income that your web-site business generates depends on two factors — the prices that you quote and how well you understand the problems of prospective clients. And you venture assumptions about the impact of those factors on income — how much income you will lose if you misunderstand the problems of 10% of your prospective clients, perhaps, and how much you will lose if your prices are 5% higher. When you review actual results for income, how well you grasped recent client problems, and the prices you quoted, those impact assumptions imply a gap in income between your goal and what you should have expected given how well you executed your strategy — the gap due to execution. The gap between what you should have expected and what actually happened reflects mistaken impact assumptions and missing factors — the gap due to strategy.

A small strategy gap means your assumptions are on target, even if execution is not so good. A large strategy gap means you need to revise your assumptions. Impact assumptions, in other words, help you answer an ancient question that complicates the lives of entrepreneurs around the world. Do I need to do more things right or do I need to do more right things? Scorecards that test only assumptions about performance do not address this question.

These days, we have so many opportunities to collect extra data that we start to believe learning depends only on how much of it we have. But it also depends on the granularity of our expectations. Rich hypotheses propel science not because they’re always right but because results cast sharper shadows on them. Big bets create great companies not because they’re always right but because they illuminate new businesses. It’s the same with what impact assumptions say about the future.

Philosophy and cognitive science of the past half century have started to investigate the dependence of what we learn on the information content of what we expect as well as the information content of our data. Hans-Georg Gadamer, father of the science of interpretation, captured the idea nicely in his 1966 essay on The Universality of the Hermeneutical Question: “Only the support of familiar and common understanding makes possible the venture into the alien, the lifting up of something out of the alien, and thus the broadening and enrichment of our experience of the world.” Managers looking for advantage in learning-sensitive businesses have in impact scorecards and other ways of testing impact assumptions a valuable tool beyond data accumulation.