Rapidly rising food prices and a global economic slowdown have exacted an enormous toll on emerging markets — making the success of micro-enterprise sectors employing the working poor all the more important. A walk through the microfinance sector in Colombia suggests that small businesses are stalling because the world’s best customers cannot find them.

Build a better mousetrap,” goes the saying, “and the world will come to you.” So for the last 60 years development economics has tilted at the windmills of poverty by trying to help people build better mousetraps.

Small business stalls

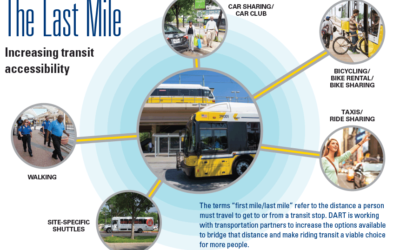

A closer look at how markets actually support micro-entrepreneurs in developing countries today suggests the economists may have got it exactly wrong. The better mousetraps are there — but the customers are not. This article will argue small businesses are not stalling for lack of ingenuity, resources or even technical assistance. It’s because the world’s best customers cannot find them.

To begin, consider some remarkable evidence that markets are supplying just the right resources micro-entrepreneurs need to start to grow small businesses.

Tale of two lenders

Everything felt normal for a microfinance institution in Bogotá, Colombia. Witness the pretty adobe building, the scrubbed courtyard with cars pulling hazardously in and out among the children at play, the guard who pointed his alarming weapon at everyone in the entrance lobby as he nonchalantly picked something from between his teeth — even the contrast between the young loan officers rushing around and the bemused and confused micro-entrepreneurs wondering where to wait. Everything felt normal for a Colombian microfinance institution, that is, until a frumpily dressed woman walked up to me and demanded in German, “Auf wen warten Sie?”

I was at the newest of ProCredit Holding’s worldwide network of microfinance institutions (MFIs), the tiny banks that make micro-loans to the poorest of the poor. ProCredit coordinates its global network from a slick semicircular headquarters in Frankfurt, but the member institutions operate independently with local management.

The case of ProCredit

Opened only six months ago, ProCredit Colombia’s main office was already buzzing with borrowers, credit analysts and finance staff. Sector maps of Bogotá were plastered across the walls. You might have mistaken it for a very busy real estate agency. While the sense of mission at ProCredit Colombia is palpable, the sense of efficient processes and controls is even stronger.

For example, one manager showed me a map with a bright line spiraling from the center out to the edges. That was the walking path one of its loan officers was to take in a new neighborhood for the MFI.

“She’ll knock on the door of every building that might contain a micro-enterprise,” explained the manager. “And the route minimizes the need to pay for public transportation!” This company wants to make sure every last micro-entrepreneur in sprawling Bogotá knows it is ready to make loans. After just six months, its customer list numbers in the thousands.

The land of coffee plantations

Cut to the lush coffee-growing region west of Colombia’s capital. The local capital, Armenia, is a strange mix of tradition and reconstructed modernity. It is enjoying a boom from high coffee prices, a period of relative peace and prosperity across the country and a rapidly developing tourism industry. It’s also recovering from the effects of a series of earthquakes, including a severe one in 1999.

Like many Colombian buildings, the offices of Actuar Quindia surround an open central atrium on two floors. Small and over 20 years old, this quiet microfinance institution seems to have grown organically with the town. Some clients have been with it for a decade.

Government missions

Driven by a strong sense of social mission and his direct experience with the wave of mass displacements dating from Colombia’s 1948 conflicts, Luis Gabriel tells us he puts what time he can spare from his responsibilities as executive director into a series of projects run for government agencies ranging from youth employment camps to skilled craft workshops.

Government contracts fully cover the cost of his projects office. A bevy of admiring female staffers flutters around Luis Gabriel as he dashes from meeting to meeting. Charity never looked so good. It was all a far cry from ProCredit’s buzzing bureaucracy.

The perfect complexity cocktail

It may not seem all that surprising to find two institutions as different as ProCredit Colombia and Actuar Quindia in the same microfinance market. But the diversity is remarkable when you consider that the microfinance sector is scarcely two decades old.

So what kind of market nurtures financial institutions as different from one another as ProCredit in Bogotá and Actuar in Armenia? The answer, I think, is a market that’s responsive to the complex mix of needs of real-life entrepreneurs.

Of course, every micro-enterprise is different — some sell fish, some repair bicycles and some build houses. But this kind of difference among micro-enterprises is not so hard for the market to accommodate. Fish sellers need inventory, repair shops need equipment and construction firms need materials — and you wouldn’t be surprised to see loans meeting all three of those needs on the books of a single bank.

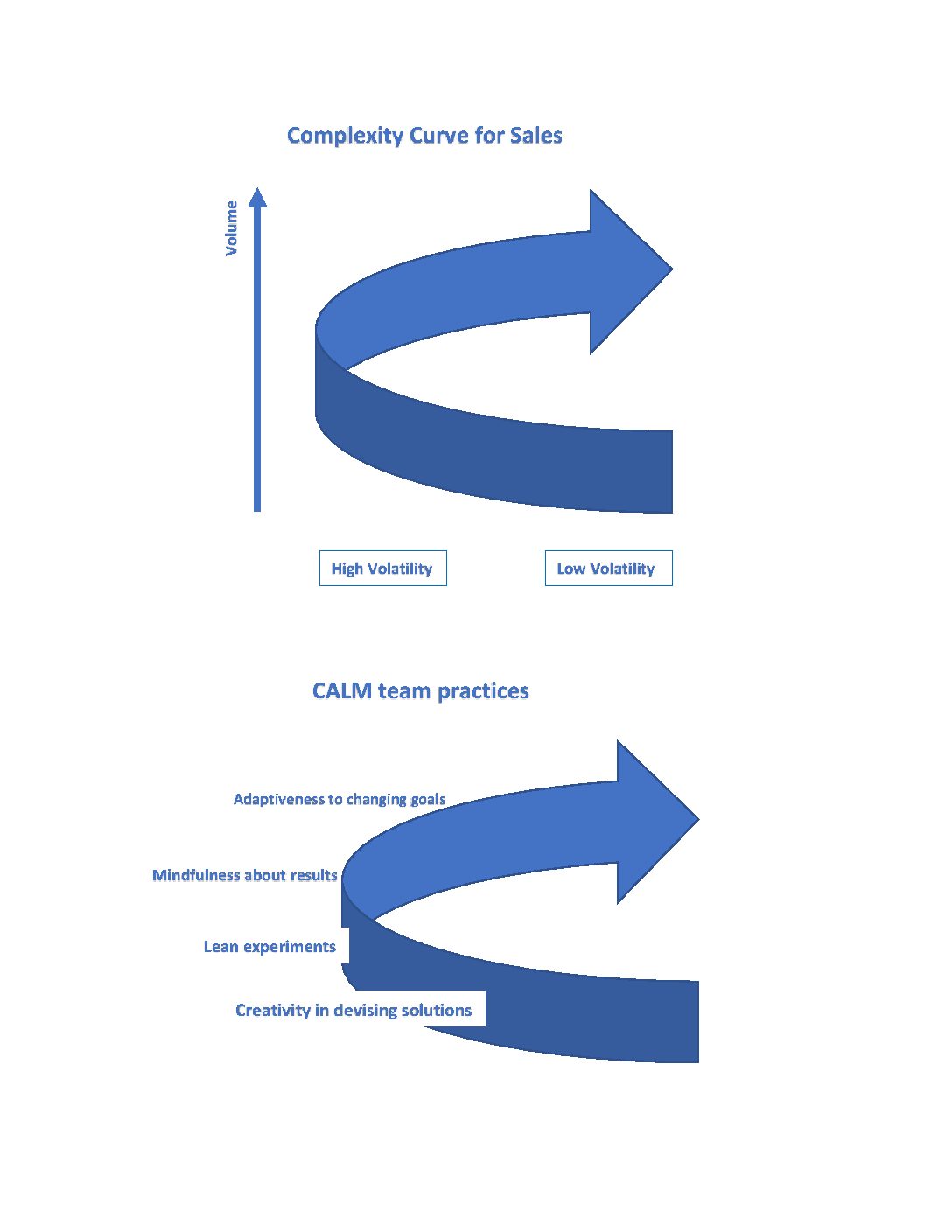

Entrepreneurs need agility…

What makes entrepreneurs’ needs complex, I think, is the delicate mix of stubbornness and flexibility that successful enterprise requires. Overly stubborn entrepreneurs run into trouble, for example, as soon as markets prove more complex than their business models.

Flexibility, therefore, might seem to be an entrepreneurial virtue of unlimited value. But even truly visionary business plans will hit air pockets, and too much flexibility can lead entrepreneurs to abandon great ideas too soon.

…and a little stubbornness

The diversity of microfinance institutions within even relatively small markets like Colombia seems to embrace the delicate mix of stubbornness and flexibility that can give rise to the greatest collective growth.

The pre-fabricated approach of ProCredit to new microfinance markets caters to the micro-entrepreneur’s need for a little stubbornness. ProCredit loan officers not only write up estimated balance sheets and income statements for each little enterprise they encounter — but they also document carefully the entrepreneur’s expectations for every month of operations. Tracking expectations is important for a micro-enterprise because it gives the business plan a little spine.

Good news — but not according to plan

For example, the reaction of a Pro-Credit loan officer to the empty cutting room of a borrower who manufactures jeans in the teeming Ciudad Kennedy barrio surrounding Bogotá’s central market was telling. Beaming, the relaxed owner told us he had sold out his entire inventory early — and would be happy to pre-pay his loan.

The loan officer smiled nervously — the loan was safe, but things weren’t going according to plan!

Entrepreneurial survivors

The customer relations of Actuar Quindia and its sister institution in nearby Caldas are looser and less formal. One borrower explained he currently was paying off a loan for his fruit and vegetable market. When we happened to ask him how he got to work, he proudly told us: “By taxi.”

“Aren’t taxis expensive?” we asked.

“Not as expensive as the parking lot across the street,” he replied, pointing at the entrance to a crammed lot. “And that’s what I’m doing with my next loan!”

He had taken out five or six loans from Actuar — never, if he’s to be believed, for the same business twice, but every one repaid with bells on.

Betting on the borrower, not the business

The little Actuar microfinance institutions in Colombia’s coffee-growing region seem to encourage something quite different from ProCredit Colombia — flexibility and survival rather than careful planning and the occasional doggedly pursued home run.

Actuar’s customers have been around for a long time, and often a lot longer than the business they’re currently running. Agility is key, which is probably good for making sure most micro-entrepreneur borrowers stay solvent — but not so good for unearthing a few business-idea diamonds encased in the mud of dozens of early setbacks.

Best of both worlds

But suppose you borrow from the likes of both ProCredit Colombia and Actuar Quindia or Actuar Caldas. Might the ProCredit loan officer’s push toward disciplined planning and the Actuar loan officer’s encouragement of market sensing and agility encourage just the right mix of stubbornness and flexibility that makes micro-enterprise sectors bloom?

If this is the entrepreneurial cocktail Colombia’s market is mixing up, it’s worth remembering the recipe — because the country is poised for an economic take-off.

Continued in “In Search of the Global Customer”.

Copyright © 2000-2008 by The Globalist. Reproduction of content on this site without The Globalist’s written permission is strictly prohibited.