What if the qualities of mind needed by successful entrepreneurs conflicted with one another? Research on best performance-management practices at the Corporate Executive Board (CEB) and program management experience at the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) both suggest this is the case.

Like development program teams that frequently change tack, Nestle has forged a highly agile approach to learning from results. And like program teams that specify a plan at the outset in great detail and make sure they execute it, Shell has used alternative scenarios to get managers to spell out their plans and assumptions in extraordinary detail. Impact scorecards meld the best of these two ways of learning from results in a single seamless process.

“Half of our teams reprogram too often,” said MCC Deputy VP for Africa Jonathan Bloom. “The moment results in one of our Compact countries fall short of target they scramble to change everything. The other half,” he continued, “never reprogram. Disappointing results can hit them over the head like a two-by-four and yet they stick like glue to the original plan.”

Bloom, a successful paper entrepreneur who has devoted himself to international development, was getting at something more than a golden mean of flexibility for project managers and business owners. He was describing two qualities of the entrepreneurial mind that are both necessary for success – and yet conflict. You can see the difference in how they each use performance results.

How to find performance indicators with predictive power was probably the most frequently asked question across the best-practices networks for finance executives that I launched and ran at the CEB. It’s safe to say that none of the members of these networks thought their firms had found a completely satisfactory way to track and learn from results. But practices at Shell and Nestle stood out in contrasting ways reminiscent of the conflicting qualities of the entrepreneurial mind that led to Bloom’s reprogramming dilemma.

Nestle presented the antidote to MCC teams that never reprogram. By 2000 the firm had thrown out its planning calendar. Any time results for any global product area in any region or major country delivered a big surprise, senior management would pause to ask which of their assumptions was most likely wrong, reset global product and overall country targets, and invite country and product managers to renegotiate their specific product-per-country targets within the global and overall totals. By pushing specific targets down to the level of an ongoing negotiation among operating managers it was easy for the massive company to revise its plans.

Shell presented the antidote to MCC teams that reprogram too often. The oil giant wanted to reward managers for ingenuity and effort. Yet one group of managers, the ones in production businesses, would seem brilliant whenever oil prices were up – while another group, in distribution businesses, would seem brilliant whenever oil prices were down. To separate out the effect of oil prices on manager performance, Shell needed to test assumptions about impact, and they tried to do so using alternative scenarios.

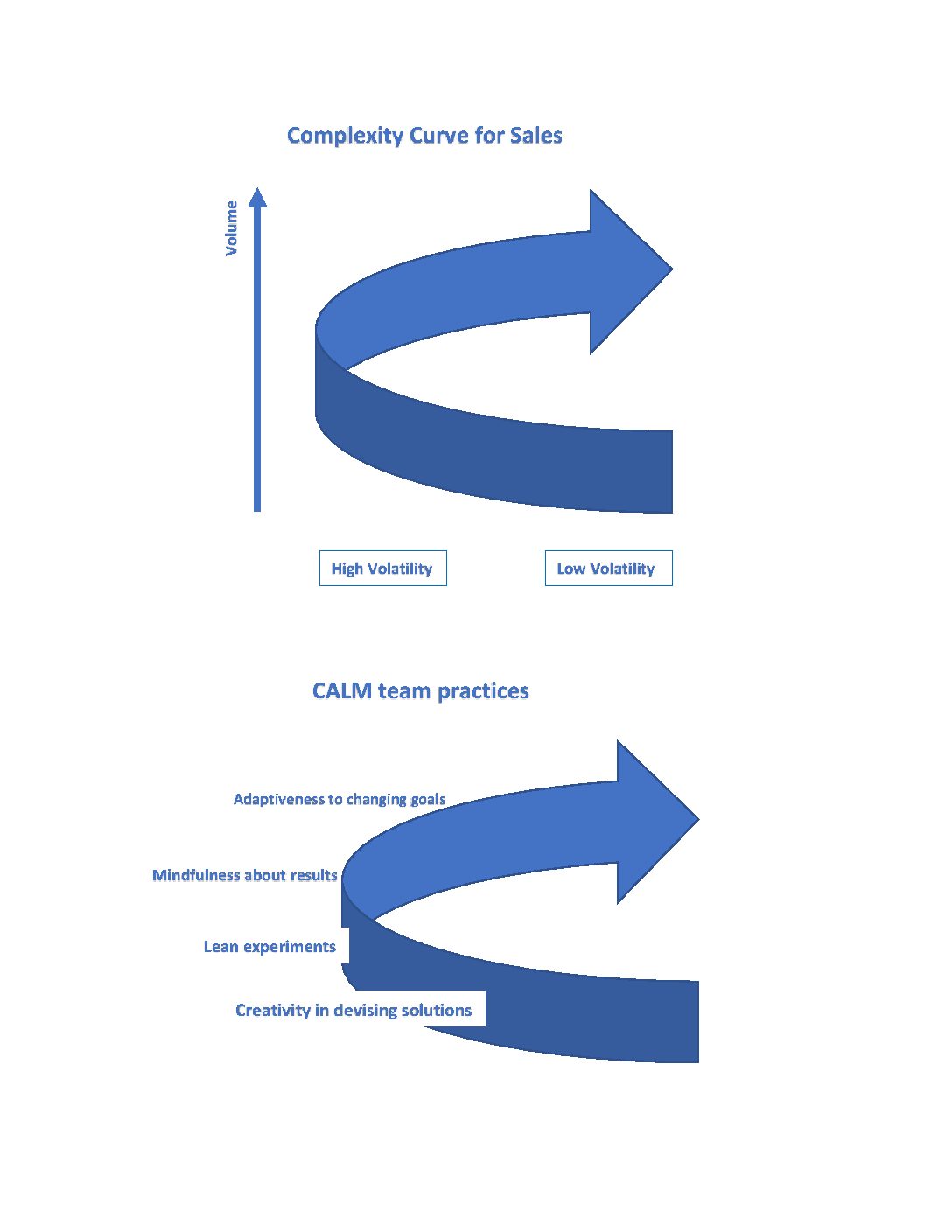

Nestle and the teams that reprogram too often represent the qualities of agility and humility that lead successful entrepreneurs to try something new – and not just try harder – when results disappoint. Shell and the teams that stick to their plans represent the qualities of creativity and boldness that lead successful entrepreneurs to lay out strategies clear enough to show any flaws quickly.

Impact scorecards integrate these conflicting leadership approaches into a single process for learning from – and reacting to – results. It’s not easy. Both approaches are needed. Entrepreneurs need to be of two minds at once.